Dear Readers,

During the month of May I will be sending you a 4-part excerpt from Chapter 1 of Sacred Selfishness, Captives of Normalcy.

Individuation: The Path to Growth and Authenticity

In understanding the individuation process and how it can work for us, it helps to know a few basic things about the levels of consciousness we can obtain. To begin with, our levels of consciousness or psychological maturity become increasingly based on self-awareness rather than age after we have reached adulthood. Unlike our physical growth, which is generally automatic, our growth in consciousness requires intentional effort, and is a process that takes us through four general stages:

- Simple consciousness

- Complex consciousness

- Individual consciousness

- Illuminated consciousness

Our development in the first two general stages of consciousness, first simple and then complex consciousness, relies heavily on the modeling done by our parents, families, and other people, and on training, education, and the development of skills. The two stages that follow, individual and illuminated consciousness, depend upon attaining a deep knowledge of ourselves and the transcendent aspects of life. For example you may have a Ph.D. in psychology, which means you are highly trained in the area of complex consciousness. But it doesn’t mean you automatically know very much about your inner life. The same thing can be said if you have a Ph.D. in theology. It doesn’t necessarily mean you have had an experience of the divine. Higher consciousness requires more than education.

No one begins life as a “conscious” individual capable of making self-responsible decisions. That identity, known in technical terms as ego-development, comes much later, and develops in stages from childhood through adulthood. Simple consciousness covers the period of time that begins at birth and encompasses the years of our early lives when our ability to learn and act responsibly is a potential slowly being fulfilled. Our parents, families, schools, churches, places in society, and the media introduce us to life in the world. They teach us that the world is safe or threatening, abundant or impoverished, educated or ignorant, a place to give to or to take from. They also teach us their perceptions of reality–for instance, “This is a vicious dog-eat-dog world,” as well as other basic attitudes covering a wide range of topics such as racial or ethnic groups, religions, and virtues.

The second stage, complex consciousness, develops as we grow through adolescence into adulthood. During this stage we become aware of and attempt to undertake the social and personal tasks that generally define adulthood. In my generation in the late 1950s, graduating from high school or college, getting married, and owning a home generally defined adulthood. My father told me, “When you get married or reach twenty-one, you’re a man and on your own.” In primitive societies, elaborate initiation ceremonies marked this transition from childhood to responsible adulthood. These ceremonies often culminated with the initiate receiving a new name and public recognition as an adult. As an official adult, the former initiate was no longer dependent upon or subservient to his or her parents and had to carry an adult share of tribal responsibilities.

Growing into adulthood includes forming and testing our identities in the temperamental forge of adolescence and young adulthood. It is a crucial period when we begin to more closely observe the world around us and the world immediately outside our parents’ sphere of influence. As we pass from adolescence into adulthood we need to discover a sense of “who we are” that we can rely on. One that has some competencies, and can persevere enough to go through whatever has to be gone through. We need to become secure enough within ourselves to separate from our parents, become self-reliant, and develop our own personal and social relationships. Technically, we refer to developing our sense of identity as ego-development and developing our ability to get along with other people at work and in relationships as cultivating our public face or persona.

Trying to work out an identity begins with models because we have to have something to identify with to get us started. Hopefully, we will discover models that fit our abilities and strengths, but this process is never easy. When I was bogged down in my sophomore year in college and couldn’t choose a major, I eventually became so desperate I chose the basic social model of getting married and thereby getting “serious” about life. Suddenly my friends and family became approving and supportive instead of worried and concerned about me. In other words I now had an identity that people could understand, not necessarily the right one, but one that could get me started and represented the “social clothes” most of us need to wear at this age.

As children we tried out grown-up identities by pretending to be doctors, teachers, nurses, and so on. We were alert to the effect the games had on the adults in our lives-whether they brought approval or disapproval. Interested uncles and aunts asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up. By age seven or eight, I learned to reply “a lawyer,” which assured a favorable response. While I enjoyed the response I had little idea what lawyers really did. I only knew it brought me validation from “big” people, and I now realize how much power this process had in affecting how I saw careers, social graces, manners of dress, and other attitudes.

By the 1970s, life had become more complicated. Few adults were asking children what they wanted to be when they grew up because the adults were either dissatisfied with their own careers, frustrated with their relationships, or rethinking their own places in life. Parents often copped out on helping children seek adult identities by telling them they could be anything they wanted to be. Children are smart enough to know that’s not true, and the lack of adult expectations and guidance often left the children floundering and unable to get on the track toward adult identities and a sense of responsibility.

Our parents’ views of their unrealized opportunities also play a role in our identity formation. My father, for example, spent a rich career as an educator. As time went by, many of the people he taught became very wealthy. On the one hand, their success gave him a gratifying feeling of accomplishment in his work. On the other hand, however, part of him began to feel wistful that he could have been more successful in business-that he could have made more money, had a higher standard of living, enjoyed more respect in the eyes of society. Part of him felt fulfilled and part of him felt resentful. As a result of this conflict he urged me to go into business rather than academics, without considering what might be the most personally meaningful career for me. We are all shaped by these two models: family and society.

A few years ago I worked with a middle-aged physician. Fred was a highly skilled doctor who was board certified in three areas. But he was wondering if he should have been a writer. In exploring his past Fred felt he had been guided toward medical school by his mother, who was a nurse. Because he was so convinced that his mother was the dominant influence in his life, I wondered about the role of his father, a retired contractor, and his hidden effect on Fred. I shared my thoughts with Fred and suggested he ask his father what he thought had guided so much of Fred’s early ambitions. A few days later Fred had a surprising conversation with his dad. He discovered his father had wanted to be a doctor but hadn’t pursued his dream after he got out of the army at the end of World War II because his wife was pregnant. His dad said that it may have been his quiet endorsement that influenced Fred more than he imagined. And, of course, everyone in Fred’s extended family and in the small community he had grown up in was thrilled with the choice. Once Fred understood the motives and circumstances that had molded his course, he felt a sense of freedom. Instead of changing careers he set about figuring out how to transform his career into one based on his values and how he wanted to live them.

Fred discovered that he could practice in a manner that fulfilled his needs to find meaning in his work by becoming more concerned with people and less science oriented. He let his intuition and feelings become part of his work on a regular basis and soon left his prestigious, high-profile practice group to join a smaller group whose approach to medicine was more compatible with his new

ideas. He also realized he could spend more time with his wife and family and still make a good living.

Stop and think about these situations for a moment. Who do you know that might have been guided to live their parents’ unrealized ambitions? What about yourself? How many of your choices were influenced by this often subtle but sometimes not so subtle pressure?

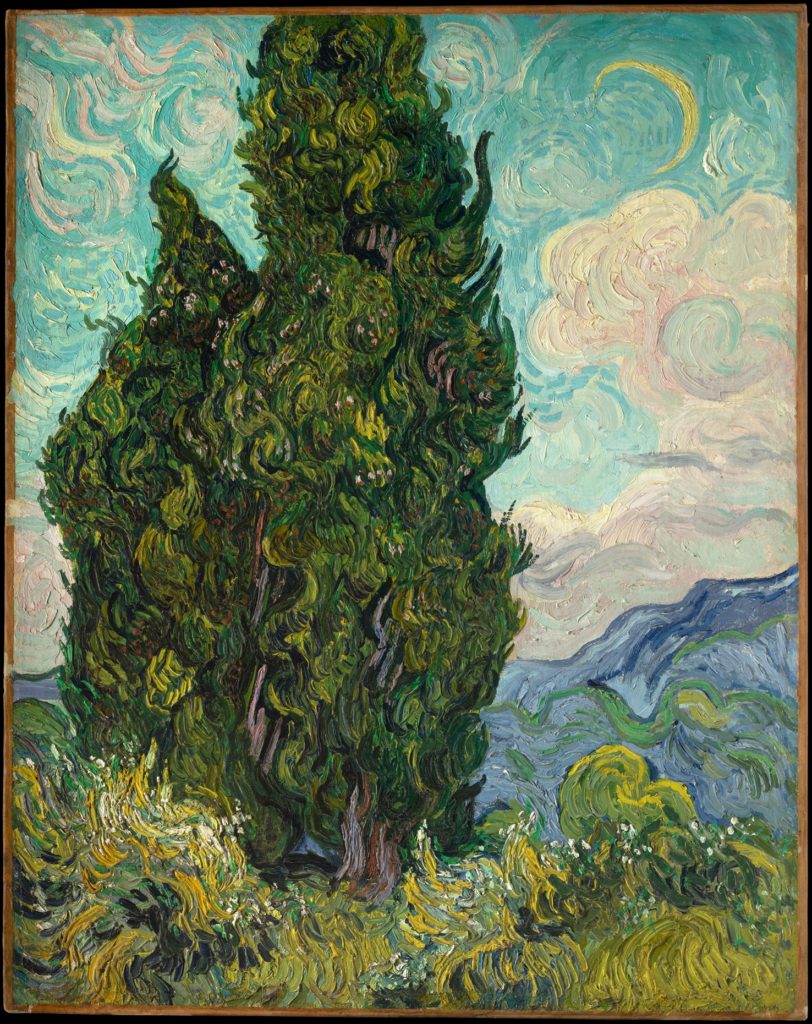

art credit: Cypresses, Vincent van Gogh

Book Excerpts and Resources

, authenticity, healthy personality, Individuation, Jung, living authentically, Sacred Selfishness

Please stay positive in your comments. If your comment is rude it will get deleted. If it is critical please make it constructive. If you are constantly negative or a general ass, troll or baiter you will get banned. The definition of terms is left solely up to us.

Leave a Reply